Whitepaper on:

Organizational Design Models: Most Common Approaches

What are Org. Design Models?

An organizational design model is simply an approach to conducting analysis and architecting the organizational structure. Models, and the firms that create them, compete for the best way to do this while maximizing benefit to the business. Another useful way to view a model is that it’s a mental framework. All strive to establish high performing teams, address span of control, and help define business units in an company.

Why are Models Important?

You use a framework to effectively work with a leadership team to approach a situation and problem solve. (It’s not just about org charts and resource allocations.) The usefulness of a model comes from two things. First, your ability to apply it in the widest variety of situations. Second, the ability to delivery results that meet business objectives. The common organizational design models described in the next section are all relatively easy to remember, so on the first point they meet the need. However, on the second point, they are all complete failures. Yes, that’s a bold statement.

Consider that for the past 40 years, organizational structure efforts have failed to meet business objectives 72% of the time (Albrecht, 2018; Ashkenas, 2013; Mimic, 2016). The numbers tell the story. If the current models produce 72% failure rates and only 28% success rates, shouldn’t we take a different approach? It’s absurd that companies continue to spend big money on big firms applying the same broken models. Honestly, you’d be better off spinning the needle in a game of chance.

Most Common Org Design Models

Each of the models described in this section propose a process and approach to analysis, diagnosis, and architecting organizational structures.

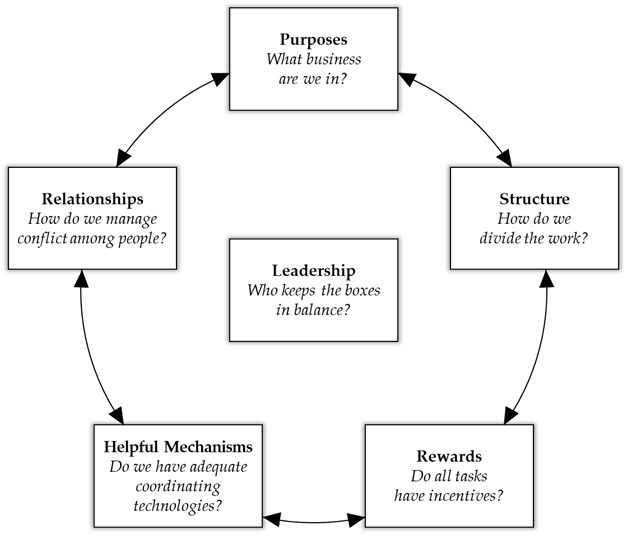

Weisbord’s Six-Box Model

Published in 1983, Weisbord’s model is arguably one of the original ones. As shown in the figure below, the six boxes are Leadership, Purposes, Structure, Rewards, Helpful Mechanisms, and Relationships. Leadership has a universal impact and association with the other five. When analyzing and diagnosing, an engagement can start in any of the five surrounding boxes. From there, it is intuitive to work around the other topics and explore gaps. This model quickly faded into the background when McKinsey released their 7S model. Very few practitioners today have even been exposed to Weisbord.

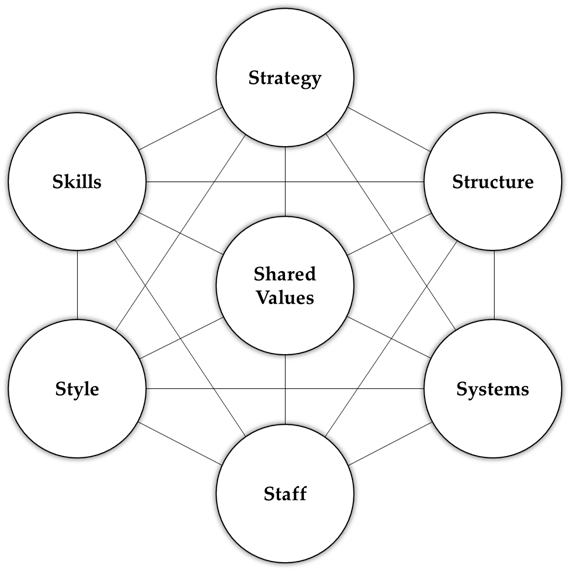

McKinsey 7S Design Model

The McKinsey 7S model was published in iterations between 1977 and 1983. It was popularized in the book “In Search of Excellence.” In some respects, it pre-dated the Weisbord model, but for the purposes of this paper we considered it a tie. The McKinsey model is by far the more popular and still retains a high degree of notoriety.

For the late 1970’s this was ground-breaking thinking born out of customer necessity. We give the practitioners praise for thinking through both cultural (soft) elements and tangible (hard) elements in the approach. The model acknowledges the systemic impact that each element has on each other element regardless of whether it’s a tangible or intangible item.

It’s also understandable and logical that values are a center point. The values that are shared in an organization impact everything that we do and how we execute our business goals. A change in values will directly impact everything else. A needed change in values will impact our ability to achieve any of the other elements.

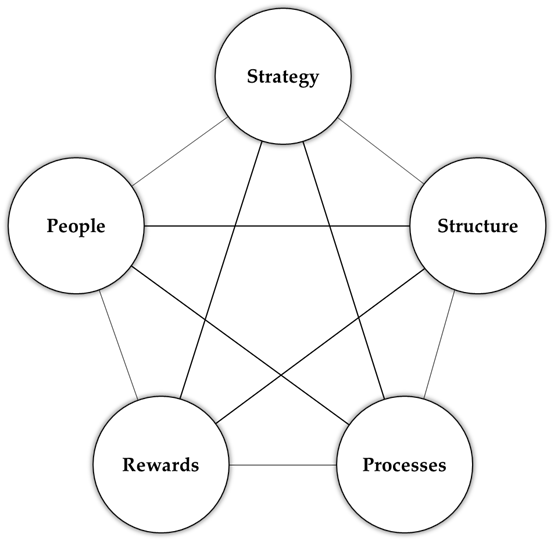

Galbraith Star Model

Dr. Jay Galbraith proposed the “Star Model” in 1994. It’s easy to see that this model is a derivative of both the Weisbord and McKinsey models. The star model gained a lot of popularity in professional groups such as organizational development and human resources. A lot of the reason for its popularity is because it’s easy to remember. Psychology research over the decades has landed on memory recall limits, and one of the more popularized limits has been 3-5 items in a list or chunks of information (Cowan, 2010). Five items in a Star configuration is a whole lot easier to learn, understand, and recall versus 7S’ or 6 boxes.

That’s not the only reason for the popularity of the star model. This model was the first one to subordinate organizational structure below business strategy. In the star model, Strategy is placed at the top because the other four elements should be subordinated to it. In that respect, Galbraith was proposing a hierarchy of sorts. It also acknowledged that organizational structure was only 1 element of many which needed to be considered to achieve a business’ goals. Of course, this was not a new proposition, as both the McKinsey and Weisbord models stated the same inter-related dependencies.

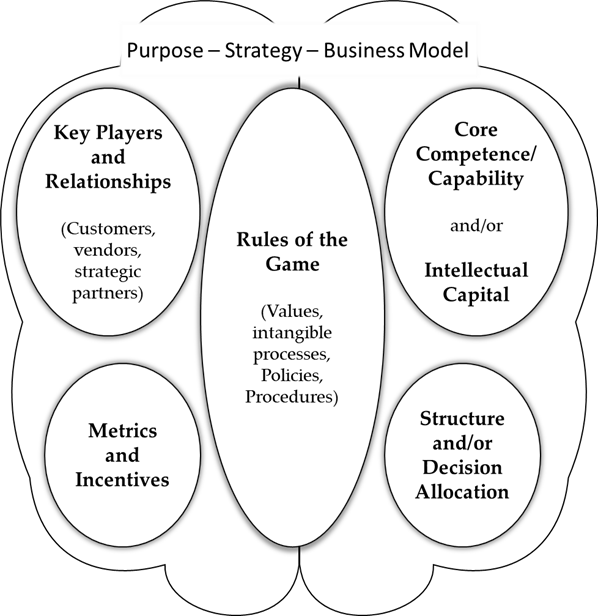

Linkage Organizational Brain Model

The “Organizational Brain” model was developed and taught by Linkage in the late 1990’s and early 2000’s. Like Weisbord, it’s a bit of an obscure model.

Again, you can see quite a few similarities to the models that preceded it. That fits with our statement earlier that these all built on each other and continued to propel the discipline of organizational to continued evolution. This is the first model that attempted to include deliberate analysis of “capabilities” and “intellectual capital.” No doubt this was a springboard off the excellent work of David Ulrich, the world-renowned author and University of Michigan professor.

This is a tough model to remember though, which is one of the reasons it wasn’t widely adopted. Each of the surrounding items was also a bit verbose, which contributes to greater difficulty remembering and applying the model. The one statement we liked about this model was being able to say, “A business’ purpose, strategy, and business model should always be ‘top of mind’.” Again though, it’s easy to see how these are building on each other and evolving over time.

Considering the Value Chain

That’s a lot of real estate in a white paper to devote to models. Especially to models which are generating 72% failure rates and are clearly failing to help businesses succeed. But, they have all contributed to an on-going body of research and they are markers on a path of discovery and evolution. In that sense they have each been very useful and beneficial.

The next evolution requires a fuller use of systems thinking. To drive high success rates, we need to anchor our efforts in the business itself. This means that we much start with the business’ operating model and approach transformation holistically. Let’s take the next steps of that evolution and bring together multiple disciplines so we can achieve much higher success rates!

Agile Organizational Transformation

We’ve pioneered an Agile Organizational Transformation approach. The word “approach” is intentionally selected here. The Agile Manifesto espouses twelve values and beliefs as it relates to software development, and this mindset is being extended into other types of product development (Beck et al, 2001). In the context of organizational design models and the case of organizational transformation, the premise of “individuals and interactions over processes and tools” is highly relevant.

Historically, as human capital practitioners, we have over-biased to models and methods, and it’s time to return them to their rightful place: inside a toolbox. When we do this, models and methods become more useful because we approach them as a toolset to be applied in the right situation. By doing so, we free ourselves to be problem solvers, which brings us to another tenet in Agile: being able to “respond to change over following a plan.”

Human Capital Management professionals are then grounded in the highest Agile priority, which is to ‘satisfy the business through early and continuous delivery of valuable organizational capabilities.’ I’ve adjusted the statement to apply to our purposes. In its original form it is specifically written to software development.

Follow us on our website or pick-up some of our

books to learn more about our approach with Agile Organizational Transformation.

© 2021, All Rights Reserved, Alonos® Corporation

To read further on the subject of organizational design, check out our book on the subject, or read an abstract of the book, and read other related articles.

Suggested Citation:

Albrecht, D.J. (2021). Organizational Design Methods: Most common approaches. (Whitepaper). Alonos Corporation. Retrieved from: alonos.com

References:

Albrecht, D.J. (2018). Organizational Design that Sticks! A multi-disciplinary approach to the business ecosystem. Dallas, TX: Alonos Corporation.

Ashkenas, R. (2013). Change Management Needs to Change. Harvard Business Review. (April 16).

Beck, K., Beedle, M., Bennekum, A.V., Cockburn, A., Cunningham, W., Fowler, M., Grenning, J., Highsmith, J., Hunt, A., Jeffries, R., Kern, J., Marick, B., Martin, R.C., Mellor, S., Schwaber, K., Sutherland, J., & Thomas, D. (2001). Manifesto for Agile Software Development. Retrieved May 2021 from: https://agilemanifesto.org/

Cowan N. (2005). Working memory capacity. East Sussex, United Kingdom: Psychology Press.

Mimic, F. (2016). Why Projects Fail? Project-Management.com. Retrieved October 2017, from: https://project-management.com/why-projects-fail/

Weisbord, M.R. (1983). Organizational Diagnosis: A workbook of theory and practice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.